How to stress less

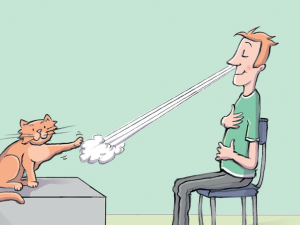

In this article we’ll show you how to deactivate the fear response that makes you stressed and how to activate your rest and recuperation response to de-stress.

We need to relax

Ever notice that when you’re stressed you make more mistakes than usual? Ever notice the same in people around you? Think about those times you’ve said, ‘Oh, wow, I can’t believe they did that. What were they thinking?’ The fact is, from a neurobiological point of view, they weren’t thinking – well, not properly, anyway. Stress inhibits rational, commonsense thinking, and now we’re going to show you how to get it back.

When my clients are highly stressed, they can’t engage or listen appropriately to anything helpful I might say. Here my initial goal changes from focusing on their issue to getting them into a state where they can think clearly and rationally. To do this, I calm them with grounding and arousal-reduction techniques – terms that describe slowing their breath and getting them into their bodies.

Relaxation techniques can reduce stress by:

- slowing the breathing rate and heart rate

- activating the parasympathetic nervous system

- lowering blood pressure

- boosting the immune system

- decreasing the activity of stress hormones

- increasing blood flow to major muscles

- reducing tension and chronic pain

- reducing headaches

- improving concentration and mood

- reducing fatigue

- decreasing anger and frustration

- boosting confidence to manage problems.

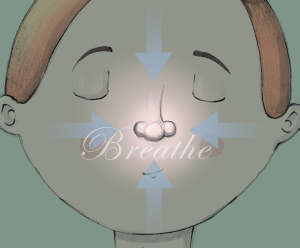

Belly breathing

To learn the belly-breathing technique you’ll need a watch, a pen and your notebook To begin, breathe normally and count the number of breaths you take in 60 seconds, counting each inhale and exhale as one breath. Write down this number.

An average relaxed adult – at rest – takes between 12 and 20 breaths per minute. Generally speaking, the higher the number, the more stressed you’re likely to be feeling. One way to reduce your stress is to breathe more slowly. Take a moment to compose yourself, then concentrate on slowing your breathing rate, aiming for 10–12 breaths per minute.

The longer and slower your breath, the more you’re activating your parasympathetic nervous system and deactivating your sympathetic nervous system, which means you’ll become more relaxed. You’re replacing the fight or flight response with the rest and recuperation response. Simple.

Once you’ve learnt to slow your breathing rate, it’s time to look at how you’re breathing. Most people are shallow ‘chest’ breathers, meaning they only partially fill their lungs. This isn’t the best way of getting oxygen into our bodies, and chest breathing happens more when we’re stressed, actually making it worse. A wide range of major health concerns is linked to poor oxygen levels, so we need to get this right.

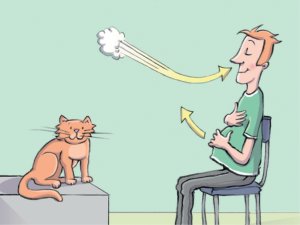

How to belly breathe

Belly breathing allows us to breathe rhythmically, effectively and efficiently so we can stop our stress response from spiralling out of control and taking us with it! Belly breathing feels nice, it’s free, it’s always available and it has no side effects. It can be really useful before an important meeting, or if you’re running late, stuck in traffic or about to have a difficult conversation. It always makes sense to be calmer and in control. To do it, simply follow the three steps below.

TIP: You might want to use a special breathing app to help you pace your breaths.

To use your breath to reduce your stress, there are three key things to remember:

- Become aware of your breathing rate – then slow it down.

- Breathe into your belly rather than your chest.

Exhale for longer than you inhale.

Belly breathing exercise

- Place one hand on your upper chest and the other on your belly. Inhale through your nose, making a conscious effort to breathe into your belly rather than your chest. To assist with this, try pushing your belly out as you breathe in, like you’re giving yourself an intentional beer gut. As you exhale (preferably through your nose), allow your belly to fall back naturally. It will help to look at your hands while you do this: the hand on your chest shouldn’t move, but the hand on your belly should gently rise and fall with each breath. Imagine your belly as an inflating and deflating balloon.

- Set a timer, and for the next three minutes focus your entire attention on the gentle rise and fall of your belly breath.

- Change the rhythm of your breath to further reduce stress. Lengthen your out-breath so that it’s longer than your in-breath. Begin with a breath into your belly to a count of four, then breathe out from your belly to a count of six or seven. Try this for 10 breaths. You can change the length of the breath depending on what’s comfortable for you right now, but the important part is the extended out-breath.

Progressive muscle relaxation

Progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) has been shown to both reduce symptoms of stress and relieve periods of insomnia. By tensing our muscles we mimic our body’s physiological response to stress and anxiety. Then by relaxing them we relieve our body from the stress response and allow our rest and recuperation nervous system to take over.

How to practise progressive muscle relaxation

It’s a good idea, before you know the technique by heart, to have someone read the steps to you, or for you to record them on a device and play them back (with your device on flight/airplane mode).

- Find yourself a warm, quiet, softly lit place. Sit back comfortably in a chair with your feet flat on the floor, or lie down if you’re hoping to sleep afterwards.

- Now work through each point below in the given order. You’re basically tensing and relaxing each muscle in your body from head to toe. As you work through, hold tension in each muscle group for about five seconds, then relax it for 10–15 seconds. Pause briefly between each muscle group. Contract the muscle on an in-breath, and relax on the out-breath, remembering to tense but not strain. As you relax each time, your sole purpose is to notice how different the muscle feels.

- Make a fist and squeeze all the way up your arm. Hold that tension, notice the tightness … and then relax. Notice the immediate ease and sense of relaxation running through your hand and fingers.

- Now bend at your elbows and tense your biceps, keeping your hands relaxed. Hold … then relax.

- Straighten your arms and tense your triceps at the back of your upper arms. Hold … then relax.

- Now wrinkle your forehead by raising your eyebrows. Hold … and then relax. Imagine your forehead muscles becoming smooth and limp as they relax.

- Bring your eyebrows close together, like you’re frowning. Hold … then relax.

- Tense the muscles around your eyes by crinkling up your eyes. Hold … then relax.

- Tighten your jaw by biting your teeth together. Hold … then relax.

- Press your tongue hard and flat against the roof of your mouth with your lips closed, noticing the tension in your throat. Hold … then relax.

- Press your lips together tightly, as if you’re puckering. Hold … then relax.

- Push your head back as far as it will go or against your chair. Hold … then relax.

- Press your chin down onto your chest, feeling the tension and strain across the back of your neck and shoulders. Hold … then relax.

- Hunch up your shoulders, and tense your neck and shoulder muscles. Hold … then relax.

- Now, take a deep breath in and exhale. Notice the contrast between tension and ease, just letting each muscle go, thinking about nothing but the pleasant feeling of relaxation.

- Take in a nice deep belly breath, then tighten your stomach muscles. Imagine you’re trying to touch your belly button to your spine. Now release your breath and let your muscles relax. Notice the sensation of relief that comes from letting go. Feel a wave of relaxation spread throughout your abdomen.

- Bring your awareness to your back muscles. As you slowly breathe in, arch your back slightly and tighten these muscles. Hold … then relax.

- Gradually tighten the muscles in your buttocks by straightening your legs. Hold … then relax.

- Tense your calf muscles by pressing down your feet and toes. Hold … then relax.

- Tense your shins by bending up your feet and toes. Hold … then relax.

- Close your eyes and continue to breathe calmly and rhythmically, allowing your belly to gently rise and fall.

- After about a minute, slowly open your eyes. You’ll notice you’re feeling very calm and relaxed, as if you’ve just had a nap. Enjoy how you feel right in this moment, then take this calmness with you into your day or sleep.

When to practise progressive muscle relaxation

- In the morning – this will make you more focused, allowing you to start your day on the front foot, especially if there’s a stressful day ahead. Note that if you’ve been dreading things or putting them off, PMR could get you in the right frame of mind to tackle them.

- During the day – PMR can ease tension from interpersonal difficulties or physical ailments like headaches, strains or even indigestion.

- Before you get home – PMR will allow you to unload the stress of the day from your body, thus cooling your stressometer and your risk of being triggered by family or evening stress.

- Before sleep – use PMR to train your body for the best night’s rest ever.

StressLess

by Matthew Johnstone

by Michael Player

If you're alive, you experience stress. It's just part of being human. For early man, stress helped us flee danger like a marauding mammoth, a hungry sabre-toothed tiger or an invading tribe. It literally helped us fight or flight. In modern society a little stress is useful, it keeps us energised and motivated to get things done, it helps us to turn up and be on time. Yet too much stress is harmful, and stress is sadly, at an all-time high.

Unfortunately, it's almost impossible to avoid or substantially reduce stress in our lives. The things that make us stressed are the same things that always have: too much work, not enough time, financial woes, family needs, navigating difficult relationships - these familiar scenarios aren't likely to change. So if we can't change the things that cause us stress, we must change the way we interact with it.

When we feel threatened or endangered in any way, our body and mind react accordingly. Unfortunately, these days our brain sees many 'threats', even if they're not actually a danger to us. This 'stress' is a major problem and is now considered to be a major precipitating factor in almost all major diseases. Yet if we're prepared to learn from it, stress can be a useful teacher. Coping with moderate amounts of stress builds a sense of mastery and it promotes resilience for life down the road.

Stressed spelled backwards is Desserts. With that in mind; through this beautifully illustrated book from illustrator and speaker Matthew Johnstone and experienced clinician Michael Player, the hope is to turn one of the most unpleasant of human experiences into a sweet one.