How to find happiness in the moment

Life is full of targets, goals, ambitions and boxes awaiting their ticks. Our relentless pursuit of external validation, our need to compete and succeed, is unsustainable. In this article, Matt Rudd explains how to find happiness and contentment in the moment.

Fitness is important. If you’re fit, life is easier. You have more energy. You sleep better. You are less likely to drop dead, because lack of exercise is the second-biggest killer of middle-aged men after smoking. It’s all really simple, route-one stuff.

But there’s fitness and then there are the fitness obsessives. Men like the marketing manager from Surrey who go for a thirty-mile bike ride before breakfast, own more Lycra than underwear, and run ultra-marathons because marathons are too short. Their moods live and die by the current stats on their running apps. I am friends with some of these people. They pop round for tea (‘Have you got herbal?’) with their rictus grins and their heavily strapped knees. ‘I’m training for the Iron Man. It’s a real killer. I love it.’ But after the runner’s high comes the runner’s low.

They’re all bright-eyed and bushy-tailed as they build up to the next insane challenge they’ve carved out for themselves. But once the glow of achievement has faded, they’re miserable, scrolling phones for the next, bigger fix. It’s their way of proving they’re not getting old. It’s denial in Reeboks. It is – ironically – unhealthy.

The solution is not to take to the sofa, feed the pot belly, drink yourself to sleep and wait for the Grim Reaper to come knocking. You can still release the endorphins; you just have to do it without a stopwatch. Go for a run because you want to, not because you have a time to beat. Go for a cycle because it’s a lovely day, not because you want to unleash your office-incubated aggression on a couple of horse-riders and an old lady crossing the road too slowly. To which my friends – doing muscle stretches in my kitchen – say, ‘I couldn’t do it if I didn’t have a target.’ To which I say, ‘But that’s the unsustainable bit. It’s why Jonny Wilkinson got depressed after making that World Cup-winning drop goal. It’s why James Cracknell should never have become the oldest rower in the Boat Race.’

As I’ve repeatedly said, this is not a self-help book but I am being helpful now. I’ve spent enough time faffing around with exercise fads to know. If you treat exercise as a challenge to be met, then you’re falling into the same trap that got us all into the midlife maelstrom in the first place. Life is full of targets, goals, ambitions and boxes awaiting their ticks. Our relentless pursuit of external validation, our need to compete and succeed, is unsustainable.

Ben Sinclair runs a health clinic in the Midlands. He spends his working days trying to convince his patients to live healthier lives. For a while, he didn’t follow his own advice, which led to the familiar creep towards midlife misery. Fortunately, his day job meant he recognised the signs, so he prescribed two simple treatments. First, he started running through a forest. It’s not a long run. He doesn’t time it or log it on an app or compare himself to other runners on the same route. But it is a proper forest – wild and beautiful and ‘when I run through it, I appreciate it,’ he says. ‘It brings me alive. And if I see a deer, I am sustained for the whole day. Men have a deep-seated need for adventure and part of what’s killing us in the modern Western tradition is that we no longer have any adventure in our lives. We are sold a car on the basis that it can drive across the savannah, but we’re only ever going to drive it to the supermarket. Where’s the freedom?’

It’s a good point. Men – sweeping generalisation klaxon – have a tendency to go to extremes with new projects. We buy all the gear, we set big, manly goals, we fail to meet those goals, and we sell all the gear on eBay. Our expectations are too high and, when the reality doesn’t measure up, the whole lot goes in the bin. The idea that you can find freedom and adventure in a fifteen-minute trot through the forest at the end of the road is inspiring – and no one has to buy a one-way ticket to Alaska. Sinclair runs through the forest for the simple joy of running through a forest.

His second treatment is even more radical, but I think you’re ready for it. At the end of each working day, he boards the train home and – brace yourself – switches off his smartphone. ‘I made the conscious decision to do something on the commute that would help my mental state,’ he says. During his phone-free journey, his focus is on contentment, something too many of us neglect. ‘Through reflection, you can find contentment,’ he says. I know that sounds wishy-washy, but I’ve tried it and it works. You make a list – an actual list with a pen and paper – of all the things you’re grateful for, including the people you love. You can even go through a meditation during which you declare your love for everyone you care for in your life. (The meditation can be whispered – we don’t want to frighten your fellow commuters.)

‘It’s not very blokey,’ Sinclair says, ‘but I find it therapeutic. It means, hopefully, that you’re not going to be a git to your wife when you get in. You’re not carrying all the stresses of the day back home with you. You made time for reflection. You’ve reminded yourself of good things. You’ve got something left in the tank.’

You may think this is all a bit much, but just try it the next time you’re nose-deep in a fellow commuter’s armpit on a late-running service due to the late running of an earlier service. The change is incremental, and you might want to save the ‘I love my wife/dad/postman’ chant with accompanying finger cymbals until you’re a pro and/or arrested. But do try it.

Delete MapMyRun, run through the forest or the wood or the park at your own pace, and make gratitude lists on the train or the bus or the escalator. Think of this as the first step in a pre-emptive strike against midlife misery. Start examining what makes you happy. It might be a short list. And things that don’t make you happy might even try to crash the party. One of them might be the idea of writing gratitude lists, which would be very unhelpful of it. But it’s all about mindset.

The psychotherapist Viktor Frankl was deported from Vienna to the Theresienstadt ghetto in Czechoslovakia in 1942. Two years later, he and his family were transported to Auschwitz. He survived but his wife and his parents were killed. When he returned to Vienna, he wrote Man’s Search for Meaning, a remarkably hopeful, inspirational work based on his unimaginably horrific experiences. The meaning of life, he concluded, is found in every moment of living: ‘Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances.’

So, write your gratitude list. It doesn’t matter how short it is or how inconsequential some of the entries may seem. It’s not like anyone else on the train will notice or care. They’re all too busy answering supposedly urgent emails from people they definitely wouldn’t put on their gratitude list.

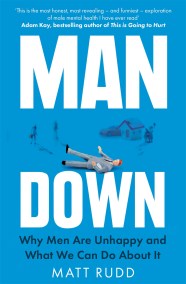

'The most honest, most revealing - and funniest - exploration of male mental health I have ever read' Adam Kay

'Matt Rudd may have written the most important book in a generation' Idle Society

'A whole-hearted and important attempt to analyse what has gone wrong for so many men and to make some tentative suggestions for what may help' The Times

'This book is essential' Sathnam Sanghera

'I love everything Matt Rudd has ever written' Chris Evans

'I loved it' Christine Armstrong

On the surface, men today don't have much to complain about. At work, they still get paid more than women for doing the same jobs. At home, they still shirk most of the unpaid labour. Putting the bins out does not count.

Beneath the surface, it's a different story. An alarming number of men end up anxious, exhausted, depressed - and very reluctant to admit they are. Even if they do everything that's expected of them in work, life and fatherhood, genuine happiness is still elusive. By midlife, their levels of stress are higher and their levels of wellbeing are lower - and work-life balance turns out to be just a cruel illusion.

The evidence is clear and ironic: the system set up by men for men doesn't work for men either. It is making none of us happy.

In Man Down, Matt Rudd takes the long view on this perplexing paradox. Drawing on stories from his own life, and the varied lives of the other men he has interviewed, he goes back to the beginning to consider what makes the modern man - how the seeds of midlife misery are sown in the school playground and cultivated through adolescence and into adulthood. By turns compassionate and provocative, Man Down asks the important question: is midlife unhappiness inevitable? Spoiler alert: it isn't.