An American Boy, a Chinese School and the Global Race to Achieve

Lenora Chu, her husband Rob, and toddler Rainey, move from LA to Shanghai. Then Rainey is accepted into Shanghai’s most elite public kindergarten, and Lenora starts noticing her rambunctious son’s rapid transformation…

As Rainey becomes increasingly disciplined and obedient but more anxious and fearful, Lenora begins to question the system: what to make of the teacher’s methods? Are Chinese children paying a price for their obedience and the promise of future academic prowess? How much discipline is too much? And is the Chinese education system really what the West should measure itself against?

The Chinese belief system around effort is one of the most important things I’ve learned from my childhood and from my time in China. From the legendary hardiness of the Communists on the Long March—a bitterly difficult, yearlong series of Red Army treks covering roughly six thousand miles, which launched Mao Zedong’s ascension to power—to the fortitude of the average Chinese student today, Chinese culture propagates the idea that anything worth accomplishing takes serious, sustained effort. This isn’t to say the Chinese don’t believe in luck or the fates as assigned by folk religion. Proper homage to ancestors can supposedly bring about a string of blessings, and of course another group of beliefs espouses that birth legacy can be determinant of fate: “A dragon gives birth to a dragon, a chicken to a chicken, and the son of a mouse can only dig a hole.”

Yet overriding this is an intrinsic belief that anything is possible with hard work, with chiku, or “eating bitter.” If there’s a goal worth accomplishing, day-to-day life might be absolutely and miserably unpleasant for a spell. It’s a concept that parents tell their children, teach- ers ingrain in their students, and China’s leaders use to motivate their populace toward the goal of modernizing China. The concept reverberates in the classroom; studies show that for kids who score poorly, Chinese teachers believe a lack of effort—rather than of smarts—is to blame. “There is little difference in the intelligence of my students,” Teacher Mao, a Chinese language teacher at a Shanghai high school, told me, his voice unwavering in his conviction. “Hard work is the most important thing.”

Conversely, Americans and Europeans are more likely to believe in innate ability. How many times have you heard a parent say, “I was never good at math, so how can I expect John to like it? He doesn’t have the genes for it.” There’s a tendency in Western culture to believe, when it comes to academics, especially something technical such as math or science, that you either have it or you don’t. “Asian and Asian American youth are harder workers because of the cultural beliefs that emphasize the strong connection between effort and achieve- ment . . . white Americans tend to view cognitive abilities as qualities that are inborn,” as a 2014 research study put it, starkly.

Anyone who studies psychology and education will tell you this is a dangerous mind-set. It’s simply not true that a child’s innate abilities explain gaps in achievement. Overemphasizing a belief in talent gives kids a free pass: “Why bother trying if I can’t help it? I simply don’t have what it takes.”

This mind-set profoundly affects the way a person lives a life. Psy- chologist Carol Dweck has devoted her life’s research to the debate be- tween intelligence and effort, and she says effort wins. “The self-esteem movement said that making children feel smart and talented would help them succeed in school,” Dweck told me, from her office at Stan- ford University. “But too much emphasis on ‘smart,’ and these kids ar- en’t motivated. They don’t persevere.”

The winning approach is clear: Instead of telling a kid, “You’re so smart,” we should say, “Good job—you worked hard.”

When I think about the Chinese emphasis on effort, I realize it de- rives in part from the modern experience. For decades, the nation has witnessed legions of youth study for the gaokao. This nationwide, her- culean effort—in and of itself—attests that the Chinese believe a high score is more likely to be the result of sweat and labor rather than some kind of inborn intelligence.

This type of mind-set has special value when it comes to learning math and science. “You have to work hard to achieve,” says Xiaodong Lin. “And the Chinese work hard.” Small, wiry, and full of energy, Lin is a Chinese émigré and a pro- fessor at Columbia University’s Teachers College in New York City. In one of Lin’s most widely cited studies, she divided teenagers trying to learn physics into three groups.

One group of students was introduced to some of the greatest scientists of our age—Galileo, Newton, and Einstein—and told of these men’s very intense efforts to develop the theories that made them famous. Newton was presented as a man whose hard-grinding, everyday work ethic led him to develop his gravitational theory. Einstein developed the earth-shattering theory of relativity, but, the teenagers were told, he also tried for the last twenty-five years of his life to establish what’s called a “unified field theory” of electromagnetic and gravitational phenomena. There he failed.

A second group of students was told only of the scientists’ lifetime achievements and nothing of the process in getting there. The control group mainly learned about the physics they were studying.

The results were clear. For certain groups of kids, hearing about the tortuous struggle of the greats increased their confidence and interest in learning physics. It was a “Maybe I can do science, too” moment.

Those kids who heard about effortless genius were demotivated. “Those who believe that intelligence is a fixed entity give up or withdraw quickly when facing challenging tasks,” Lin wrote. “People who believe that intelligence is malleable and can be increased incrementally with effort are more likely to hold learning goals in school.”

Westerners could take a page from this playbook, Lin emphasized. “Americans think that if you have to work hard you’re not a genius. You see it in the news headlines all the time: ‘Extreme Success Without Struggle.’ ”

This attitude creates problems in the classroom, says James Stigler, the UCLA psychology professor: “In America we try to sell this idea that learning is fun and easy, but real learning is actually very difficult,” said Stigler. “It takes suffering and angst, and if you’re not willing to go through that you’re not going to learn deeply. The downside is that students often give up when something gets hard or when it’s no longer fun.”

The Chinese teacher who wants to present a difficult problem has it easy, Stigler told me. “The Chinese teacher can just say ‘Work on it!’ and the students will suffer, they’ll struggle through it, they’ll be uncomfortable. The Chinese have socialized their kids to put up with suffering and discomfort and all the things that are a really important part of learning.”

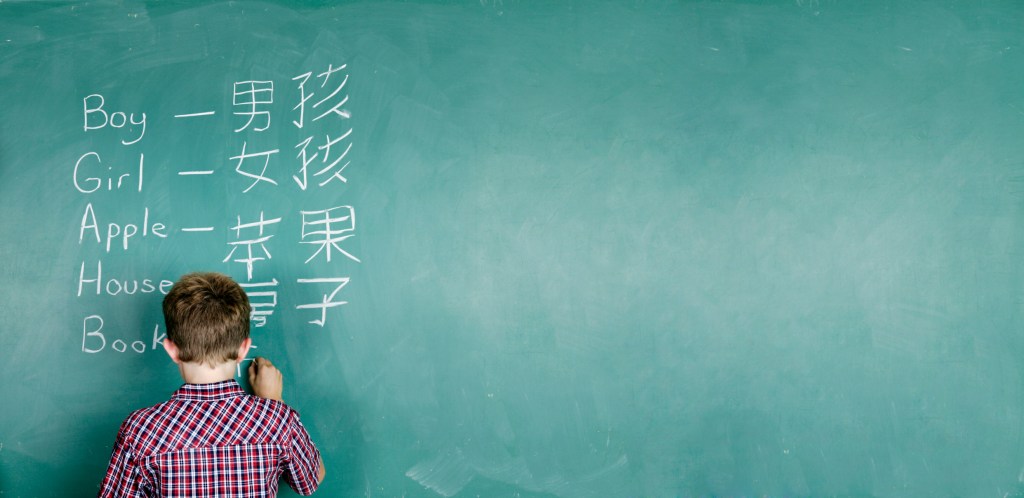

During a Minnesota high school visit, I met a Chinese teacher who’d bumped up against a clash of culture while teaching Mandarin to American students. Short-haired, with an easy smile, Sheen Zhang was nothing like the image of an authoritarian Chinese teacher she had as a child growing up in Xi’an, the Chinese city famous for its terra-cotta warriors. I told her so, and she laughed. “I started out very controlling, but I noticed that if I yelled, my American students rebelled,” she said. “They talked back!” Sheen made other observations: Her students couldn’t sit still for an eighty- six-minute class, parents complained when she assigned too much homework, and she had to “make the classroom fun and enjoyable.” Ironically, Americans are on the right track when it comes to athletics. “It’s all about getting better, getting better, working harder,” Jim Stigler said. “In sports, we’re okay with competition and struggle.”

And the American conscience is okay with rankings in sports. “A ninth-place finish simply indicates a runner should retool and con- tinue training—a ninth-place finish doesn’t reflect poorly on a person’s self-esteem or worth,” Stigler said. “But in academics, you don’t want to embarrass someone by ranking them Number Thirty because ‘It’s not their fault.’ In American academics, ‘you either have it or you don’t.’ ”

“That’s too bad.” At this, Stigler, sitting in his UCLA office, rapped his knuckles on his desk.

The above is an extract from Little Soldiers by Lenora Chu (Piatkus, 2017)